Variations Tend Toward Cartesian Product

Variations Tend Toward Cartesian Product Variations Tend Toward Cartesian Product

Variations Tend Toward Cartesian ProductTop is struggling towards communicating his thoughts; however, the page title points towards a very deep mathematical result: variations (in an extremely general sense) tend towards a Bell Curve. In other words, towards the Central limit theorem. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_limit_theorem

Top may not get the above, but it is quite on topic.

Perhaps it can be viewed in terms of which percent of changes are "random" and which fit a known (domain) pattern. Nor is it entirely a statistical issue because computers must handle uncommon conditions almost just as well as the common ones. It's often just as much code to handle the 1% case as it is the 99% case. People who are not programmers often don't get this and think in terms of human labor or manual processes, in which case quantity distribution matters more.

It's perhaps all part of a bigger field or question: What are the patterns in domain variations on a theme that affect software design decisions? If we are designing software to be easier and less risky to change, we must understand how things tend to change over time. How do we identify, represent, and catalog these patterns? -t

I have been trying to find a concise way to convey what I observe about "variations on a theme". I have called it "interweaving factors" in the past, but this was not clear enough. The variations tend not to fit hierarchical classifications nor interchangeable blocks (PolyMorphism), at least not "large blocks". Instead, the pattern of variations tends toward a CartesianProduct of all combinations of features. Sometimes there is a grouping or even a hierarchy of sorts, but it tends to either be short-lived or subject to the EightyTwentyRule.

For a simplified illustration, suppose we have 26 potential features of a given "thing" (master template, master class, etc.) Suppose we represent each of these features with a letter of the alphabet. Uppercase means the feature is active for a given instance and lowercase means the feature is not active. Thus, the variations would tend to look like:

AbCDeFG... aBCdEfg... abCDEfG... AbCdEfg... aBcdeFG...such that there is no real or lasting pattern beyond the potential existence of a given feature.

And, there is a kind of fractal nature such that sometimes we have to split the granularity of variation, and that new granularity will also tend toward a CartesianProduct of combinations. For example, if C has to be sub-divided, we can get:

C1c2C3... c2C2C3... C1c2c3...-- top

And I think, that this view is just a result of thinking in tables. Sorry, no teasing intended, there is nothing wrong with that view, its just, that it disregards that ItDepends. It depends on

"Features" is not a database-specific thing. Even if you try to make a generic widget, you will find that to make it handle more UseCases it often has to have more features. This is claiming that the actual usage pattern of the features is more or less random, or at least too random to try to add discrete groupings to.

Further, if my view is shaped by "thinking too much in tables", then couldn't other paradigms do the same thing? Why would you be immune? I've tried to study patterns to see if I could put things into hierarchies and polymorphic swappable modules. It just won't fit, at least not lastingly. The real world appears too capricious and random (LifeIsaBigMessyGraph). This is a statement more about domain needs than about technology.

Just make all the features active and be done with it.

Like Microsoft did with those [bleep] smartquotes and auto-formatting? Implementing that many features up-front may also be a pain in the arse (YagNi violation).

Based on a UseNet discussion:

> Business applications change and grow like any other application. As > they do there are modules that wind up being duplicated and then > modified because new function A' is a lot like old function A except > for ... OO can really help eliminate the duplication in situations > like this.I've studied the patterns of changes and variation re-occurrence that I see over the years. I have concluded that the generation/creation patterns of variations tend to be a *Cartesian Join* of all possible features. There may be *some* rough treeness, but not enough to rely on in the longer run.

Thus, say there are 26 total features, and we label them from A to Z. The variations would then tend to be random subsets of the features:

instance 1: A,C,R,Q,V,Y instance 2: D,J,L instance 3: C,G,R,T,V,Z instance 4: E,F,K,L,M,P,R etc.....The procedural/relational approach is generally to put the feature lists in tables, and then a task will tend to look something like:

Task Foo(...) {

if A {....}

if B {

if K {...

} else {

...

}

}

...

if Y {....}

if Z and not M {....}

} // end-task

It ain't pretty, but I have not found something better (a BusinessRulesMetabase perhaps could be considered, with caveats). It does not have a "clean ladder" shape, but rather which features affect which block tend to vary. For example, 3 features may affect one action and only 1 feature affects the next, etc. Further, the IF structure tends not to be the same from task to task. Polymorphic solutions tend to assume the same IF "framework" for each different task, which is the incorrect assumption most of the time. The "If" framework will likely be different from task-to-task. Thus, the "same ladder" structure found in say OO shape examples does not apply.

I am curious, assuming this is an acurrate representation of the variations (if you disagree, save that for later), what would be a polymorphic or OO solution?

By the way, a more detailed description of this can be found at http://www.geocities.com/tablizer/struc.htm.

-- Top

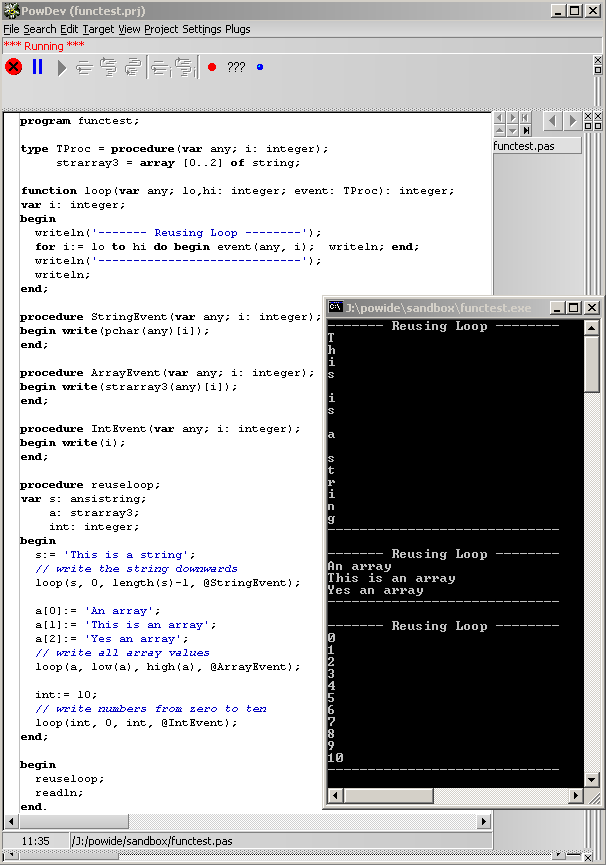

Functional proponents sometimes propose ideas that also seem to go against this principle. Suppose we have a lot of loops that are similar but not identical. Functional proponents often propose passing in the middle of the loop as a parameter (HOF). However, this is too big of a chunk of variation in my experience. Thus, I tend to lean toward something like this:

function loopyThing(ftrA, ftrB, ftrC, etc...) {

// parameters are "features"

loop_setup...

while (loop_condition) {

if ftrA {...}

if ftrB {...}

if ftrC {...}

etc...

}

clean_up...

return(...)

}

This way the features can be treated as non-mutually-exclusive. Some may suggest turning the features into HOF's, but again complexity does not chunkify nicely in that way either. The loop above may eventually grow to something like:

while (loop_condition) {

if ftrA {

if (ftrB) {...}

else if (ftrD || ftrF) {...}

else {...}

}

if ftrB {...}

if ftrC {...}

if ((ftrC || ftrA) && ! ftrF) {...}

etc...

}

Unless you ignore duplication factoring, these are the kinds of things one sees in practice. The granularity of variation can be very small such that swappable "chunks" often just don't work. You either have to duplicate a lot of similarities, or make them very small in order to pass in HOFs. Plus, I'm not sure defining the internal loop contents (as HOF's) outside of the loop where they are used makes much sense. If the inside of the loop gets too large, then moving some of it to subroutines can be done.

The main point of passing a HOF for this is not that the insides of the loops are any easier to deal with; it's that you don't have to keep writing/testing/debugging the same loop control construct over and over.

Duplicate loop control construct code was not an issue in the scenario above. I suppose one could trade one for the other to some extent, though. But if most of the variation is inside the loop, then the above issue may apply because the variation boundaries are smaller than the inner loop block size. HOF granularity may still be an issue, but we would probably have to investigate it on a case-by-case basis.

MopMind? says: if a loop is duplicate an imperative language, then there are ways to reuse the same loop and swap in a "chunk". See how I pass in a procedure/function as a parameter the loop (an event or trigger) below. Also, if a For Loop supports High() and Low() or a forEach (ensuring boundaries are not out of range), then the loop is not as error prone. Loop structures in imperative language clearly mark code as a loop control structure. In functional programming it's hard to tell what the heck is going on, because everything is just a function inside a function, inside a function (naming the function loop can help, but it seems coders aren't this obvious).

It could be argued HOF functions are hard to debug because there are so many functions that the code doesn't read clearly for different control logic. In addition, some imperative languages support limited closures, and can utilize recursion, but many programmers seem to avoid recursion for readability where a loop could be used instead. See my program below for a reuse of the loop example. I think this is academic and causes unreadable code in some cases (which is why many people don't do functional programming, no offense).

Also, swappable chunks are kind of related to ParametricPolymorphism, IncludeFileParametricPolymorphism - as one can make use of the same loop by using these techniques. I still however wonder if these ideas are mostly academic - how many times do we really reuse the same code and at what cost of lessened readability? Still, interesting to think about.

I'd argue that you are not reducing code size in any significant way. The "loop" call is approximately just as complex as a FOR construct itself. Plus, it is less familiar to many developers. One should not add behavioral indirection like that unless it buys you enough to compensate for the added complexity and the MentalIndexability tax of deviation from common convention. FOR-loops are also more self-documeting than that function call. The position of the parameters in the loop call are not very friendly either. We could improve that by making named parameters, but then it looks almost like a FOR-loop; meaning you've essentially reinvented the FOR wheel. The messy ChallengeSixVersusFpDiscussion looks into a similar issue. --top

In the context of CeePlusPlus, one way of adding the changes one by one is to use PolicyBasedClassDesign. -- JohnFletcher

That is perhaps bordering on ReinventingTheDatabaseInApplication, which is also what VisitorPattern leans towards doing. I'd rather manage bunches of relationships via a query-able tool rather than hard-wire all those in app code. That way I can study it from different angles, sorts, filters, etc.

See also: LifeIsaBigMessyGraph, ChangePattern, PredicateDispatching, CombinatorialExplosion, BusinessRulesMetabase, FeatureBuffetModel

EditText of this page

(last edited December 24, 2012)

or FindPage with title or text search

EditText of this page

(last edited December 24, 2012)

or FindPage with title or text search