I'm proposing the concept of Kolmogorov Quotient as a calculable number that represents the amount a high-level language reduces the complex. That is, the amount of expressivity or succinctness of a programming language. This idea of "simplification" is a factor of text-wise reduction (fewer characters needed to express a complex concept, à la AlgorithmicInformationTheory) and another, less easy to quantify concept of maintainability. Fleshing out this latter concept, it is clear it has to do with how easily one can establish programmer consensus for the given task (i.e. how many programmers of the language would put it back the same way you've expressed it or otherwise agree on the best implementation for a given problem?).

It is a Quotient so that higher Kolmogorov numbers for a given language denote a reduction in the complexity of solving the problem in the given language.

How do you propose to calculate the Kolmogorov Quotient?

Well, once the basic premise/methodology above is agreed to, it is only a matter of a rough constant addendum of difference for any specific implementation. (That is, as long as the implementation is the same across all measurements, the number should be valid and comparable.) But it could go something like this: Pick a language "close to the machine", like C or Assembly, and measure the amount of bytes of machine code it generated to implement a standardized suite of common, independent, programming tasks(*) (base_language_count). Then code the exact same functionality in the target language (no external libraries allowed) and count the number of bytes of source code (test_language_count).

KQuotient = (base_language_count / test_language_count) / number_of_equivalent_programs. - MarkJanssen

number_of_equivalent_programs is the number of programs fluent programmers of the language agree that are the best and equal solutions to the problem. (In case it's not clear, equivalent programs are those whose output is the same for all inputs.) This accounts for the "Perl problem" (I hope), because although fewer characters are required for many tasks, they would have 50 different implementations.

This should always be greater than 1.0. {why?} I'd guess Python or Ruby has the highest Kolmogorov Quotient.

[As for "why?": if your ProgrammingLanguage isn't reducing the complexity of programming an operation beyond the machine code (or even C) equivalent, there's no point in creating it.]

- First, a language doesn't need to reduce complexity for every program (and logically, by the pigeonhole principle, cannot). Second, even if we operate at the 'suite' level, any suite of programming tasks is likely to be biased - e.g. favoring procedural languages, or dataflow languages, or logic programming languages, or languages with good concurrency models, or languages with good IO models, etc.. Third, "bytes of source code" is an extremely incomplete metric of complexity, e.g. not adequately addressing the issues of debugging, documentation, validation, maintenance, extension; large variable names, explicit typing, and assertions, for example, may worsen the KQuotient but improve other metrics for complexity.

Programming languages are not necessarily about reducing the complexity of performing an operation beyond the machine code equivalent. Sometimes they're about providing a way to express problems more easily. Sometimes the former and the latter are the same thing. Sometimes they aren't.

So you actually calculated your KQuotient here, or are you guessing?

Python? Really? It's a rather conventional imperative programming language, with roughly equivalent expressivity to any other. What about Haskell? Or Prolog? Or even CoffeeScript?

[Sorry you jokers. A shorthand on top of

CommonLisp has to win this one (trivial macro to rename the long names to really short names).]

Lisp cheats (edit: on a VonNeumann achitecture): it uses recursion and hides all the actual machine code cycles it takes to run the program. Also: making macros to cheat at source length would count against you on the other heuristic: maintainability or "programmer consensus".

Huh?

....Unless you're running on an actual Symbolics machine. But no-one does.

Show me the machine code for a recursive factorial function on standard hardware. I bet it will be larger than the iterative version. If you're not going to limit yourself to such hardware, the KQuotient concept is probably inapplicable or, at minimum, would have to be reformulated for SymbolicComputing?.

On a modern architecture with instructions for procedure calls, the machine code is not going to be significantly larger than the iterative equivalent. It might be slightly slower and less efficient. Of course, any recursive function can be converted to an iterative equivalent, but a solution is often much easier to express recursively. Isn't expressiveness, rather than efficiency, the essence of your KolmogorovQuotient?

- Sorry, I don't know what I was thinking; with TailRecursion, a factorial function can be made into a fairly trivial "iterative" version (or I think more accurately called a "jump call with continuation").

"On a modern architecture..." -- un huh, recursive functions require arbitrarily large stacks, iterative procedures never do. Show me a CPU ("modern architecture") that has an unbounded stack. None. Thank you. You have to emulate stacks in software, so you have to include that code in your count. Next time, I'm going to ask you for the

AckermannFunction, 'ya bastid. (I chose a bad example above, as the factorial function can easily be written to use

TailRecursion. <snap>....Now I'm going to have to make sure the

test suite includes a non-primitive recursive function....)

- Iterative procedures can also require potentially "endless stacks" or queues -- iterative tree traversals, for example.

- No they don't. Are you just making shit up?

- How would you do depth first searches of trees of arbitrary depth, without a stack of size equal to the depth of the deepest tree? What if you don't know the depth of the deepest tree? If the depth of the search trees is unconstrained, which is quite reasonable, then doesn't successfully traversing them require an (essentially) "endless stack" independent of whether the algorithm is iterative or recursive?

- That problem was solved long ago in ComputerScience. The solution is to simply count. If you're not familiar with ComputerScience, you shouldn't be arguing about languages.

- How does "simply count" work to determine tree depth, exactly? I think you'll find it requires a tree traversal, which brings us back to the same problem.

- Each time you cross over a node, you increment the counter. This is where the CeeLanguage might be instructive to you.

- I am quite familiar with C, but do not see its relevance here. What do you mean by "every time you cross over a node, you increment the counter"? Where/how are you getting each node to "cross over"? How does that find the depth of a tree? Please illustrate your algorithm with code.

There are architectures (which is not necessarily limited to the CPU, but is typically dependent on the operating system as well) that allow stack sizes up to the limit of available RAM. Of course there can be efficiency issues with recursive solutions, but in cases where that is not an issue, recursive solutions may be more expressive than their iterative equivalents. That's why we use them.

- All such stacks are emulated -- they require more code than you're acknowledging.

- What do you mean by "all such stacks are emulated" and how is it related to my point about the expressiveness of recursive solutions? Expressiveness is about the code you write, not about the code the compiler emits. Isn't the KolmogorovQuotient about expressiveness, or to use your words, "the amount of expressivity of a programming language"? If so, even if some technique emits more code from the compiler than another, doesn't that simply mean the technique that emits more code has a higher KQuotient number?

- No.

- Why not?

- Because the KQuotient is a factor of both source code, and emitted code. If you have to emulate a stack, then that code counts against you. Additionally, I'm making a specific point of using a non-tail recursive function, so you won't get a away with just one stack. Such recursive solutions are expensive on standard hardware, (i.e. VonNeumannMachines?).

- Why should the amount of emitted code matter? And why are you only now adding this as a criterion?

- {Modeling a stack is cheap. Doesn't matter whether it's an explicit class or an implied procedure-call stack; it still doesn't involve much code. But as far as this dubiously useful 'KQuotient' is concerned, only the actual code for the stack (and NOT the runtime stack size) is relevant.}

Intuitively, I doubt your KQuotient would be useful as a general measure of language expressiveness, because you can almost always find a problem for which language <a> is more expressive (has a higher KQuotient) than language <b> and another problem where language <b> has a higher KQuotient than language <a>. It might, however, be a useful way of comparing languages given a particular problem.

I don't think that will be that much of a problem -- I believe one will be able to find a more-or-less agreeable set of "suites" to test languages with. The key for a fair comparison though will be to separate out the functions which require graphical I/O (computation towards the user) vs computation towards the machine (like scientific computing).

Anyway, it's obvious that among well-known, mainstream languages, SQL, Prolog and APL are tied for first place, Haskell is second. Python and Ruby are so far behind they're not even in the race, along with C, C++, C# and Java.

- "Obvious", n=1?, otherwise see ComputerScienceVersionTwo.

- SQL is expressive? Seriously? Unless I'm missing something the only thing you can do with SQL is get data in and out of databases. You can't actually compute anything (can you?). It even fails on things you might expect it to handle like Bill of Materials. NickKeighley

- SQL is highly expressive relative to the imperative (and probably iterative) code that would otherwise be required to express the data definitions, joins, aggregation, selection, projection, updates, concurrency handling, etc. that SQL (and its associated DBMS) can express (and automatically optimise) declaratively. Most SQL implementations embed a TuringComplete procedural language, so anything that can be computed in a general-purpose language can be computed in SQL.

- [SQL with SQL/PSM (which is an optional part of the SQL2008 standard) is TuringComplete. So are versions of SQL that contain extensions that allow one to name and recursively use named subqueries. E.g. CTE. This doesn't have much to do with expressiveness which is more about how much code you have to write to get it to compute something than what it can compute.]

- I suppose my problem is with "most SQL implementations embed a TuringComplete procedural language". Said TC language is optional and not standardised. Seems to me I get better portability if I treat the database as a persistence layer (hidden behind an abstraction) and do the hard stuff in a real language (C++, Python etc.) NickKeighley

- What if the "hard stuff" you prefer to do in "a real language" has to process terabytes of database data that are too bandwidth-intensive (and/or too security-sensitive) to transfer from DBMS to client? What if the "hard stuff" functionality has to be shared across a large number of (possibly geographically distributed) applications written at different times in different programming languages that are maintained by different development teams? These are typical enterprise requirements, and some of the reasons SQL (usually) has StoredProcedures -- so that data-intensive and/or security-sensitive server-side functionality can be developed and deployed once in the shared DBMS instead of on every client.

- in fact isn't this really saying that SETPLs (SQL Embedded Turing-Complete Languages) are more expressive than OPLs (Other Procedural Languages)? Why is this?

- The non-procedural parts of SQL allow the programmer to express functionality in a declarative syntax that would otherwise require much more imperative code. So, pure declarative SQL is the most expressive. Pure imperative procedural code is the least expressive. In between, in terms of expressiveness, we find declarative SQL plus imperative procedural code where necessary.

- "*" "suite of common programming tasks" can be broken down into two categories:

- Data Processing Suite (i.e. simple text I/O) -- computation towards the machine

- GUI Suite (tasks requiring graphical I/O) -- computation towards the user

I believe this list is exhaustive.

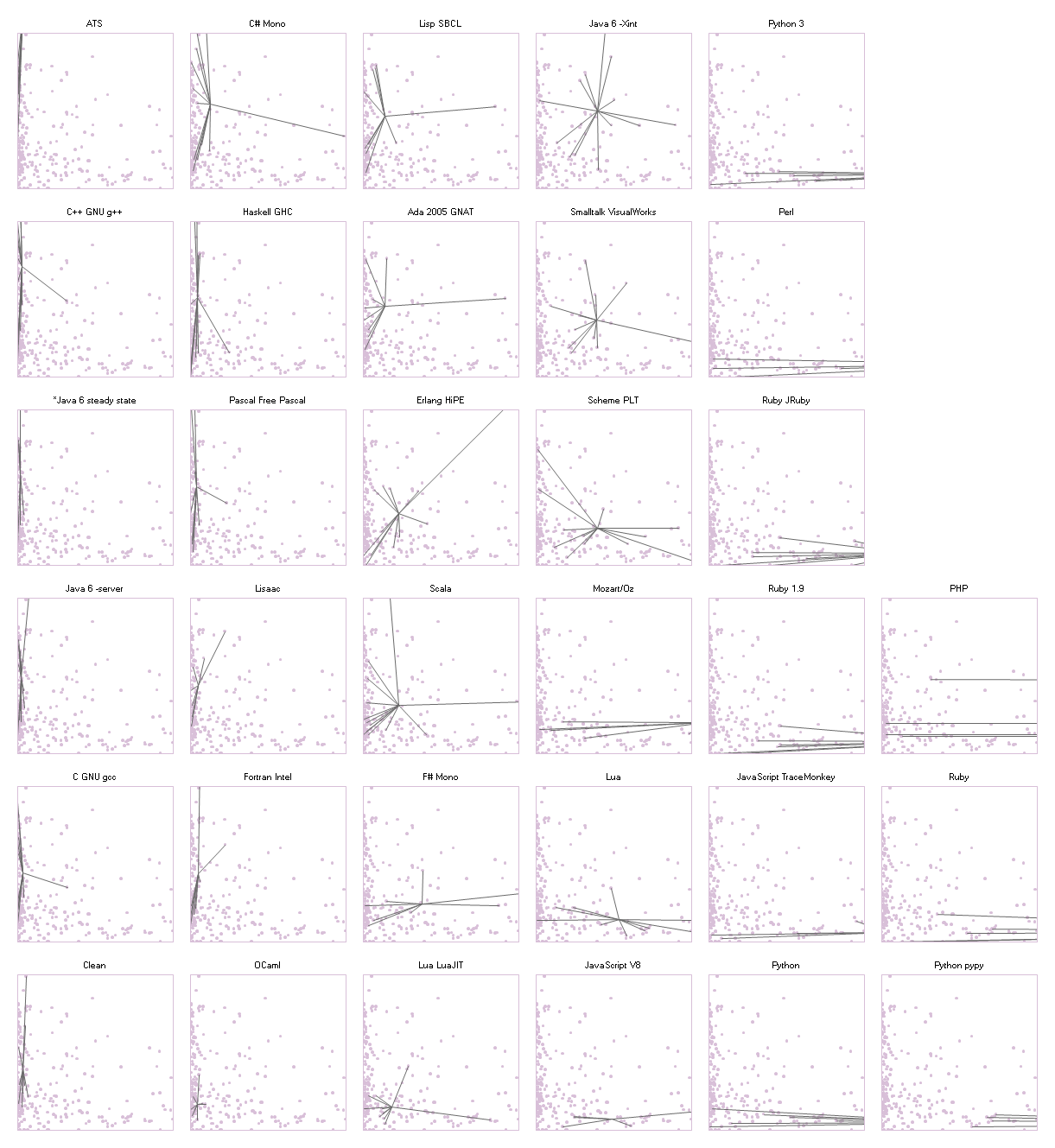

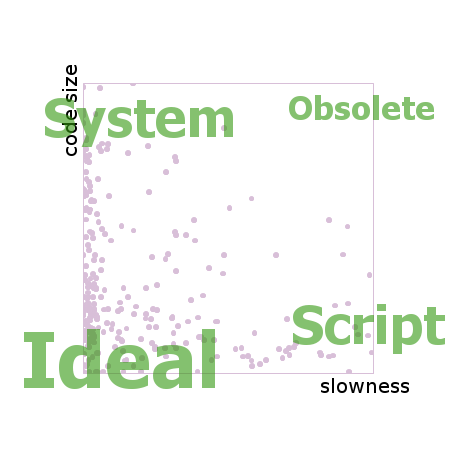

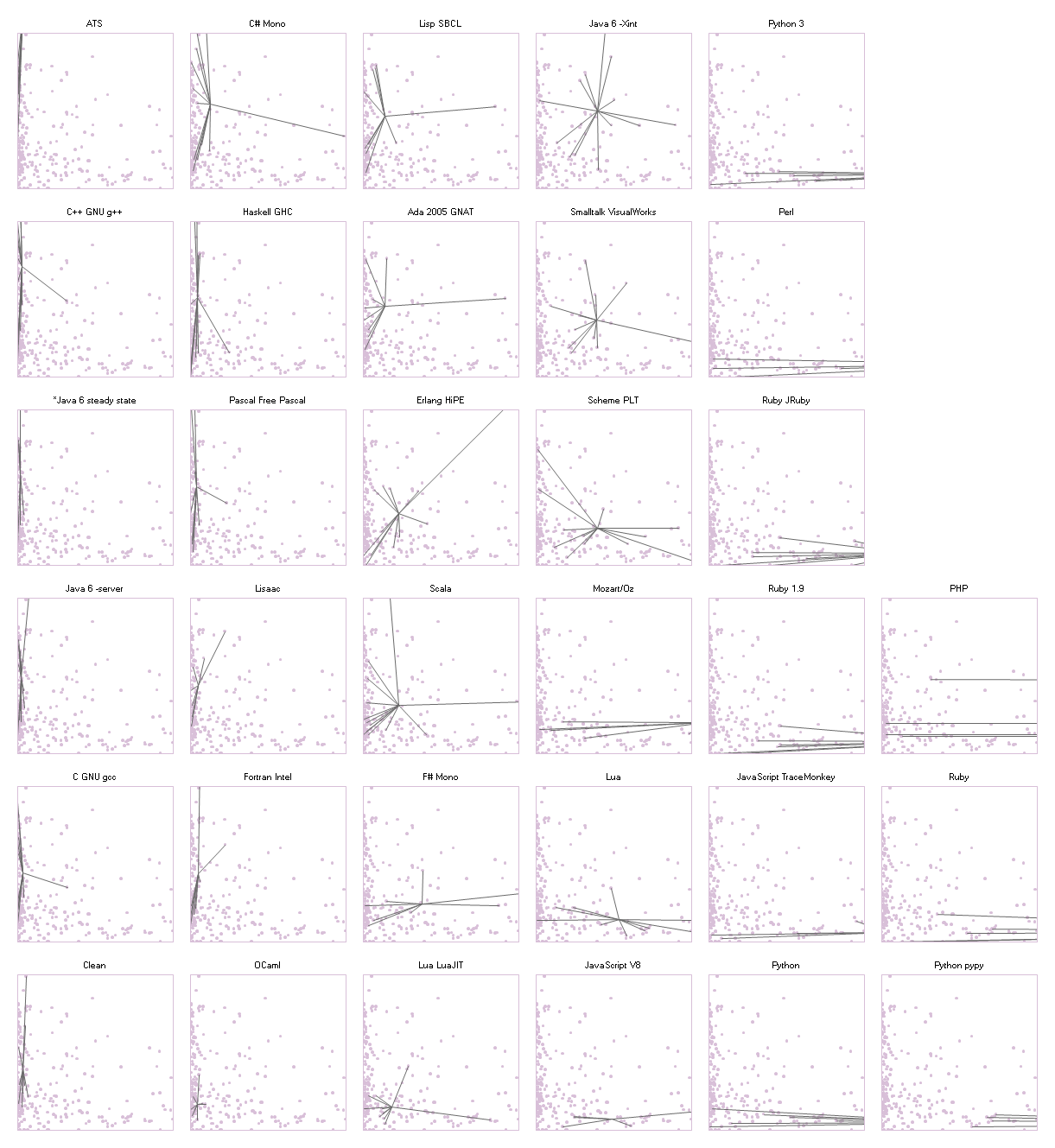

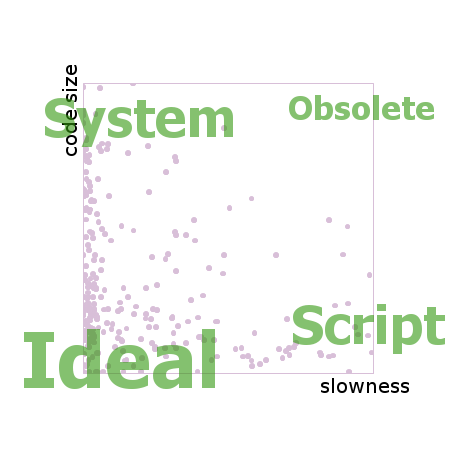

I'm not sure what good KolmogorovQuotient will ever be. But comparing code sizes can be entertaining, and there was a decent analysis from the shootout a while back: http://blog.gmarceau.qc.ca/2009/05/speed-size-and-dependability-of.html

Legend:

Well, as you can see, you've proven my point: Python, Ruby, Perl, and Javascript have the smallest code size for the same functionality. But that is just one factor of the KQuotient (maintainability, the other). I suppose measuring the concept of "maintainability" has to be fleshed out more, but I think you could assign each symbol a special number indicating it's significance, then measure NxN symbol/letter difference between different but equivalent implementations with these special multipliers (something like a[M]x[N]) and then...

[And Python, Ruby, Perl and Javascript are all slow. Ocaml, on the other hand...]

Haha, yes, but you see once we decide on a language, we can engineer the hardware to make it fast. Until then it would be a PrematureOptimization to focus on speed because the world really doesn't know what it wants computers to do yet.... ;*)

{That's an optimistic assertion given the historical failures to distribute specialized hardware or sufficiently smart compilers.}

Related, see this article on programming language expressiveness: http://redmonk.com/dberkholz/2013/03/25/programming-languages-ranked-by-expressiveness/

In particular, the following graph shows more expressive languages on the left, less expressive on the right:

Of course, some of the above are not programming languages per se, or at least not general-purpose ones. E.g., Augeas is a language for manipulating configuration files, and VHDL is an electronics description language for specifying hardware.

Interesting, thanks.

See KolmogorovComplexity, LinesOfCode

AprilThirteen

Kolmogorov Quotient

Kolmogorov Quotient Kolmogorov Quotient

Kolmogorov Quotient

EditText of this page

(last edited December 1, 2014)

or FindPage with title or text search

EditText of this page

(last edited December 1, 2014)

or FindPage with title or text search